HARLEY, STEPHEN W.

HARLEY, STEPHEN W.

(Steve) (1863–1947)

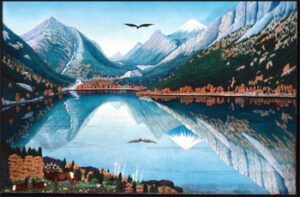

was a painter who revered nature. He was born to William and Mary Ann Lee Harley of Fremont, Ohio. The family moved to Scottville, Michigan, in Harley’s boyhood, and it was there that the artist’s lifelong love of the outdoors began. Although he inherited a dairy farm as a young man, Harley took no interest in itsoperation, preferring to roam in the woods while a caretaker tended his cows. His interest in wildlife inspired him to study taxidermy, and he preserved carcasses for both pleasure and income.In the 1880s or 1890s, Harley took a correspondence course in drawing and drafting and began to paint. By the early 1920s, financial problems, alcoholism, andinvolvement with the caretaker’s wife prompted Harley to leave Michigan for the Pacific Northwest, where he visited Washington, Oregon, northern California, andAlaska. The area’s magnificent scenery inspired Harley to take several photographs, but, according to tradition, he was disappointed with the results, and tried oil painting as an alternative means of recording his impressions.When Harley returned to Scottville in the early 1930s, he brought with him the three landscapes on which his fame rests today:

Upper Reaches of the Wind River

(painted near Carson, Washington),

Wallowa Lake,

and

South End of Hood River Valley

(both of the latter painted in Oregon). All of these paintings incorporatevistas of great depth, yet all are so meticulously detailed that, in some cases, one can count the leaves on the trees. Rich, saturated colors also distinguish these scenes. Cultivated fields dominate the foreground of

South End of Hood River Valley,

while the other two are unmitigated celebrations of wilderness.Harley kept these three landscapes with him through the beleaguered last years of his life.The family farm was lost in a mortgage foreclosure, and Harley had only a small dwelling for shelter; for income, he drew twenty dollars a month from the state’sBureau of Old Age Assistance. (Later, that sum was reduced to eighteen dollars a month.) He had ceased painting upon his return from the Northwest, possibly because of crippling arthritis. In the end, coronary heart disease and arteriosclerosis put an end to the life of the man who, on the back of one of his paintings, haddescribed himself as “The Invincible.” Harley never married, died childless, and no one attended the funeral that saw him laid to rest in an unmarked grave.

See also

Painting, American Folk; Painting, Landscape

.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bishop, Robert.

Folk Painters of America.

New York, 1979.Dewhurst, Kurt C., and Marsha MacDowell.

Rainbows in the Sky: The Folk Art of Michigan in the Twentieth Century.

East Lansing, Mich., 1978.Hemphill, Herbert W. Jr., and Julia Weissman.

Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists.

New York, 1974.Lipman, Jean, and Tom Armstrong, eds.

American Folk Painters of Three Centuries.

New York, 1980.Lowry, Robert. “Steve Harley and the Lost Frontier.”

Flair,

vol. 1, no. 5 (June 1950): 12–17.Rumford, Beatrix T., ed.

American Folk Paintings: Paintings and Drawings Other Than Portraits from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center.

Boston,1988